Written by Brent Fafeita, History Curator – Museums Wellington

The British and Irish Lions roar into Wellington this week. With the city primed to host and play its part in the historic rugby series, it’s good to remember that Wellington’s connection with Panthera leo (lion) is far more extensive than just that played on the rugby pitch. In fact, although obviously not native to New Zealand, ‘lions’ feature prominently throughout Wellington, past and present.

Most people acknowledge both the value and importance of the lion to the balance of life and diversity in the animal kingdom. Zoos across the world host lions in their stocks as a means to educate the public and safeguard the species. Wellington Zoo is no exception. Two of the Zoo’s historic lions stand proudly in The Attic at Wellington Museum – King Dick (1898-1921), the Zoo’s first lion and currently on loan from Te Papa, and Rusty (1977-1997), the Zoo’s last lion to undergo taxidermy. Together their kingly presence highlights the change in thinking away from taxidermy to a greater emphasis in education and animal welfare.

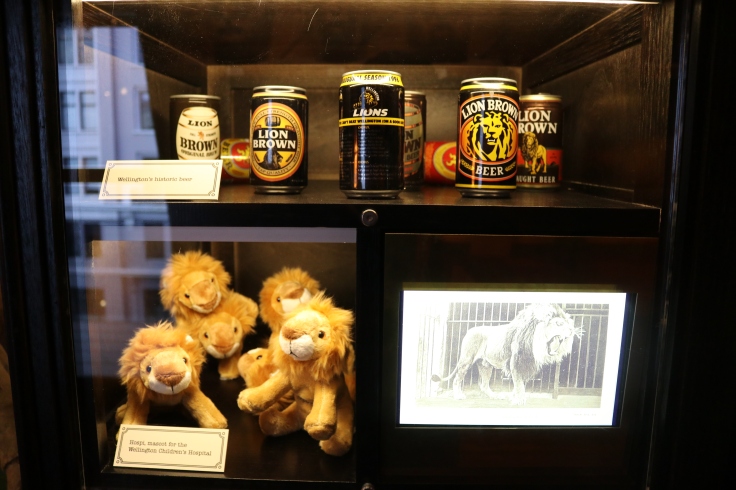

The lion is more than an animal however. Displayed alongside King Dick and Rusty are other mementos from the material world that evoke the lion, such as Margaret Mahy’s (1936–2012) popular A Lion in the Meadow publication, the Wellington Children’s Hospital mascot Hospi, and other lion memorabilia and merchandise. As a symbol of strength, leadership and dependability, the lion features prominently elsewhere – it is entwined within the Wellington City Council crest and is also the symbol and mascot of the Wellington Lions (provincial) rugby team.

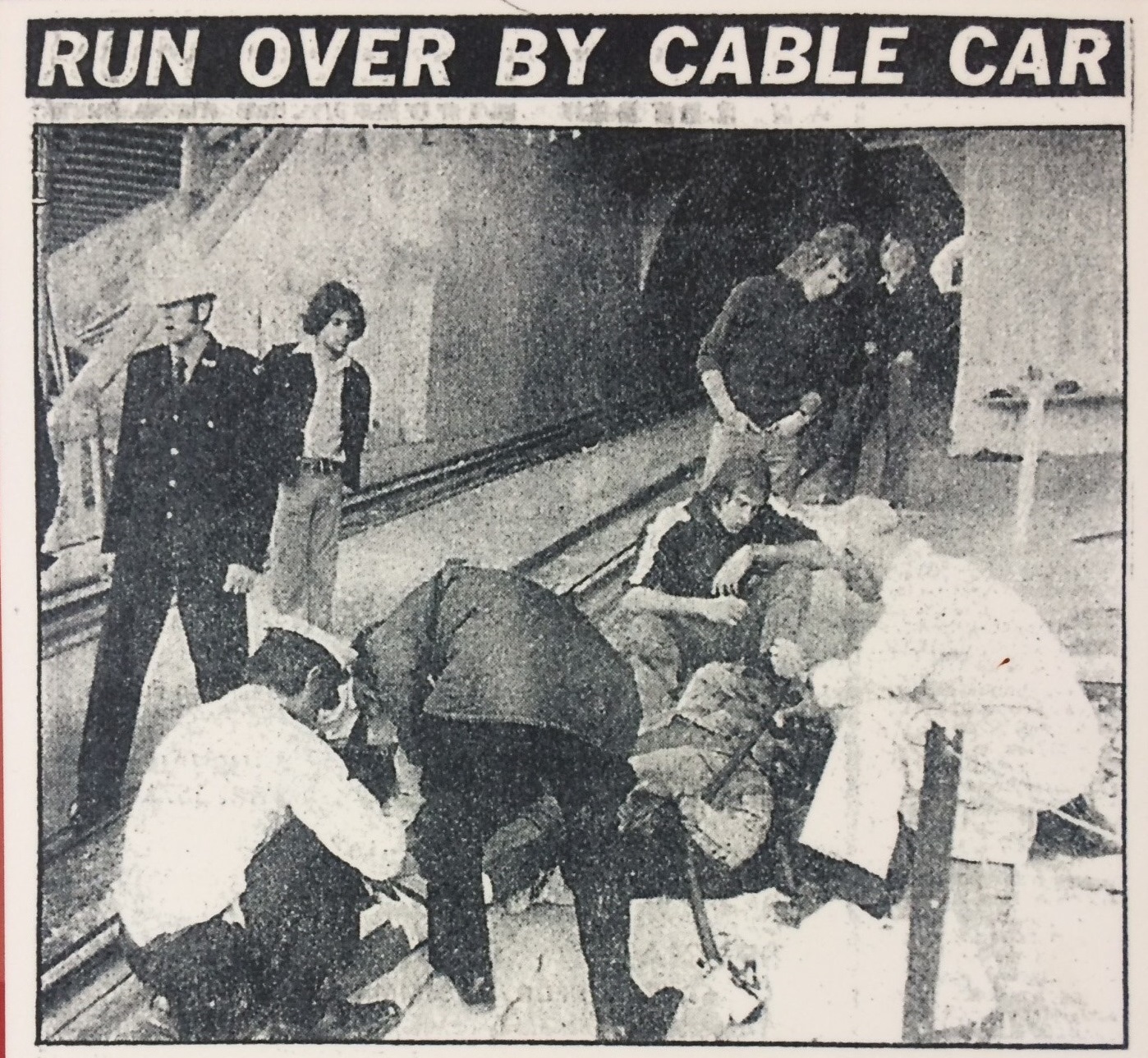

It defies belief then, that with so much attention, attribution and source of inspiration that the species is under threat from extinction. Perhaps their plight is mirrored in past lion extinctions from Wellington’s history. Premier Richard Seddon, known also as King Dick for his ‘lion’ qualities, faced challenging political times late in his career and succumbed to mortality in 1906. Lion Brown, once a treasured beverage served in pubs across the region and a fierce rival to Lion Red (Auckland based), is now a distant memory. With the challenges of the modern age, let’s hope the British and Irish Lions don’t reach a similar fate for a host of reasons. Most of all, for the combative tie with New Zealand’s homeland.

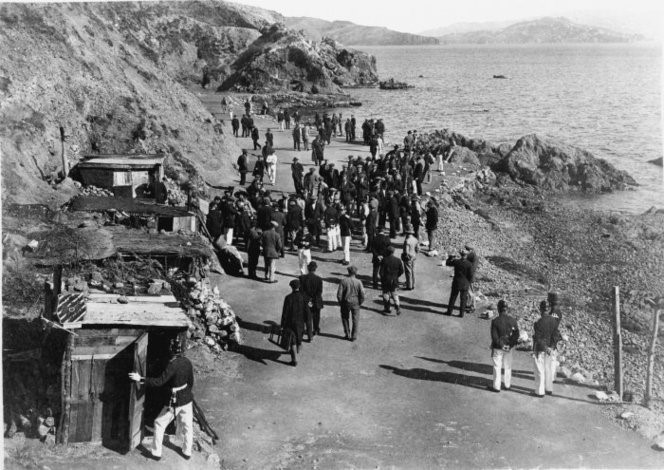

Such connections between homeland and colony stretch across years, events, peoples and interests. Wellington Museum tells aspects of this story with England and the historical lessening of those ties as other immigrant groups arrived. Some groups, like those from India, have their own animal avatars – the elephant. At the start of the 20th century many New Zealanders saw themselves as ‘cubs’ with ‘Mother’ England represented by the lion. Now as a nation, we align more with the flightless but staunch kiwi.

The act of associating ourselves with a symbolic feature of our environment is a measure of the human condition to need, and search, for belonging and identity. This is also evident with sports team names. Often, these names have humble beginnings but their meaning grows into something far greater than intended and becomes entrenched far deeper in more people than just those playing on the pitch.

That’s not to say every name has identical characteristics. Take the team names featured this week for example. Reasoning behind the Lions is understandable and already stated. The Wellington Super Rugby team, the Hurricanes, found meaning in a weather event heavily symbolic of the area. And the All Blacks, derived from a misspelt term during New Zealand’s first British tour in 1905, depict a silver fern, an icon of native New Zealand flora. Lining these and other symbols up against each other based purely on the symbol, and ranking order would likely be far different from that of their team. Above all, a name is only a name, for it is the legend behind the name that matters. Conversely, the weight of a name can be immense and burdensome – the British and Irish Lions know they harbour legendary status, but they also have much to prove.

And therein lies the crux – just as the animal species is threatened, so too is the Lions rugby concept. If the animal is allowed to wane and the symbol allowed to diminish, will the rugby battle also lose attraction? Both iterations of the lion are equally endangered if the original lion, the animal, is not treasured so. The same importance we place on the symbol should be conveyed in protecting the species.

There is cause for hope however. The Lions valued contribution to the first All Blacks test on this tour is evidence of that, as too are their supporters that epitomise camaraderie and passion. Likewise, there are great examples of progress in lion conservation and education such as that happening at Wellington Zoo. Wellington’s future lion connection appears in good hands. Needed however is more support from those with big wallets and more importantly, those with big voices. The future may be uncertain with challenging times ahead for all types of ‘lion’, but what is certain, is that the lion in all of us can make a difference.

Just stand up and roar.