By Jay Èvett

Ask any Wellingtonian to rattle off a local legend from their day and you will get different stories depending on when they grew up. You may hear about tooting in tunnels, Japanese submarines in wartime Wellington Harbour or speculation over the identity of a certain fountain-bucket thief. However, one source of stories remains constant across generations – the early days of the Wellington Cable Car. But as with all urban legends, sometimes spinning a good yarn can get in the way of the facts. I’ve gathered together the top five tales you’re likely to hear about the Cable Car and tried to set the record straight about what really happened: are they fact or fallacy?

Tall Tale 1:

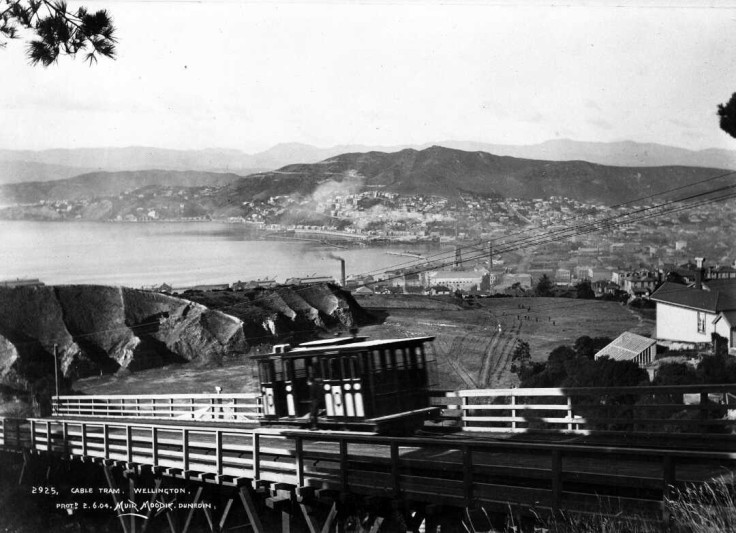

The Cable Car was built amidst a web of backdoor deals and shady agreements

FACT: The Cable Car’s early days are a web of conveniently interlocking business interests and political back-scratchings. There were so many intricate deals cut that it’s impossible to capture the full picture, even a century on. For example, whenever the line’s construction was delayed by the Council, heavily critical articles were published in the New Zealand Times to put pressure on them to cease the delays. The same newspaper purchased a plot on Lambton Quay, which it then leased to the Kelburne & Karori Tramway Company to build its lowest cable car terminal and offices – offices which were occupied by directors of the company, one of whom was a leading board member of the New Zealand Times. See, complex – and that’s just one small part of the web.

This net of convenience was cast so wide that there were few influential personalities who weren’t connected to the project, from former mayors and newspaper editors to business moguls and even a Prime Minister!

Tall Tale 2:

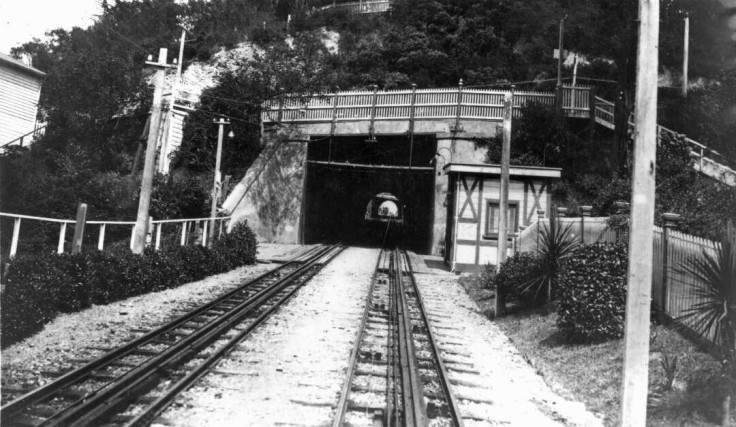

The Cable Car engineer’s young daughter was the first person through each tunnel

UNVERIFIABLE: While there are multiple reports that Vera Fulton – engineer James Fulton’s 11-year old daughter – was the first person to pass through all three tunnels, there are no contemporary sources confirming this. What we do know is that Fulton’s tunnels were plagued with bad luck, casting significant doubt over whether this claim is true. A delicate and precarious job by nature, once two work gangs connected their tunnels in the middle it was common for the smallest worker to be sent to check its integrity. This highly dangerous task brought with it the potential for a section of the wall to collapse – something Fulton knew all too well as it happened several times during his work on the Karori Tunnel.

Did James Fulton allow 11-year old Vera to undertake this risky task not just once but thrice? We may never know but we’re more than happy to hear from anyone who could verify this tale for us once and for all!

Tall Tale 3:

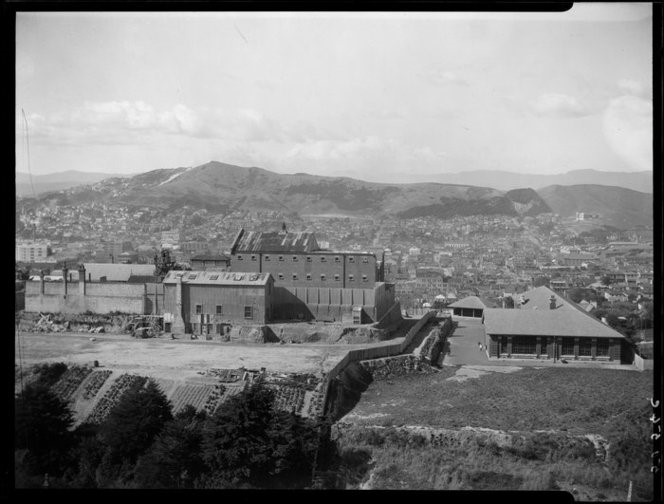

Victoria University was bribed by the Cable Car to build in Kelburn

FACT: Believe it or not, even institutions of higher learning were not above the power of the Pound. After searching for a location for its new campus, in 1901 Victoria College decided to build adjacent to the Cable Car line, abandoning plans to build in Mount Cook. What changed their mind? A liberal £1,000 ($178,000 today) ‘donation’ from Cable Car investor and Northland suburb developer Charles Pharazyn was offered to the College, on the condition that their campus was built in Kelburn. [E1]

This was to the despair of Mount Cook residents, who had been hoping that Victoria College would convert the former Mt Cook Prison into their primary campus. However, thanks to Pharazyn’s ‘generosity’, the iconic Hunter Building opened its doors in Kelburn three years later and in doing so ensured a steady stream of customers to the nascent Cable Car for years to come.

Tall Tale 4:

Prisoners were used in the construction of the line

FALLACY: Contrary to popular belief, prison labour was never used during the Cable Car’s development. Tunnelling was a highly precise skill that was in short supply during the line’s construction. It’s unlikely that a significant portion of the Terrace Gaol’s population were skilled tunnellers (who hadn’t yet tunnelled their way out of the prison itself!). Likewise, with dynamite used extensively to blast the line into Kelburn Hill it is just as unlikely anyone wanted to risk convicts handling anything explosive. This myth appears to have been inspired by prison gangs building infrastructure in Kelburn, at the time mistaken to have been working on the Cable Car line, as well as the use of the infamous ‘convict bricks’ from the Terrace Gaol brickyard to form the tunnel walls.

Tall Tale 5:

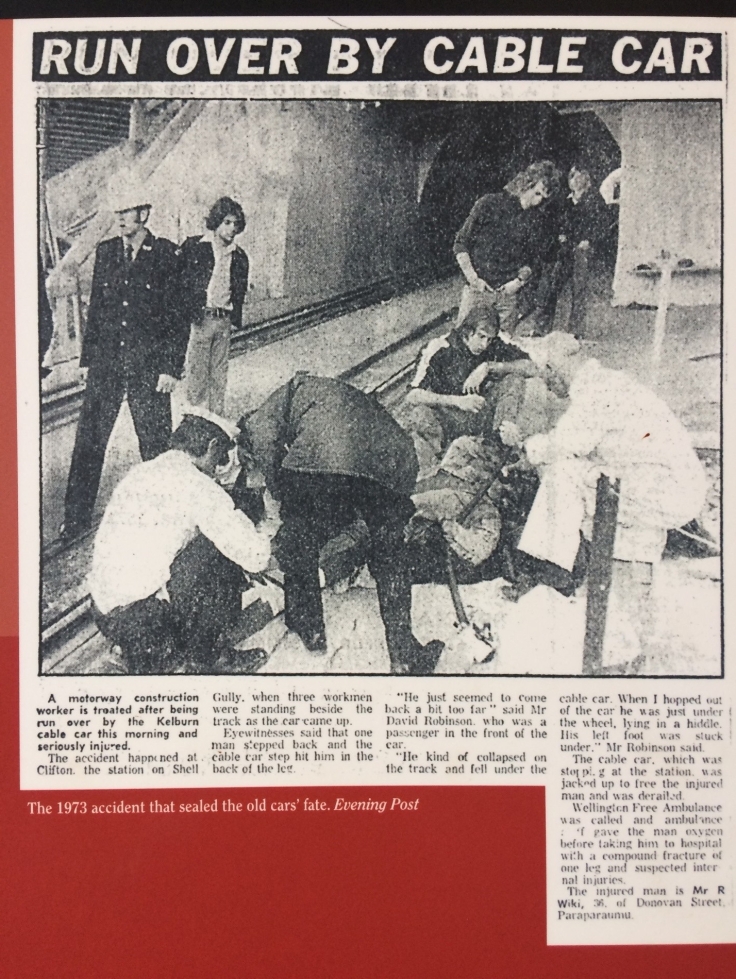

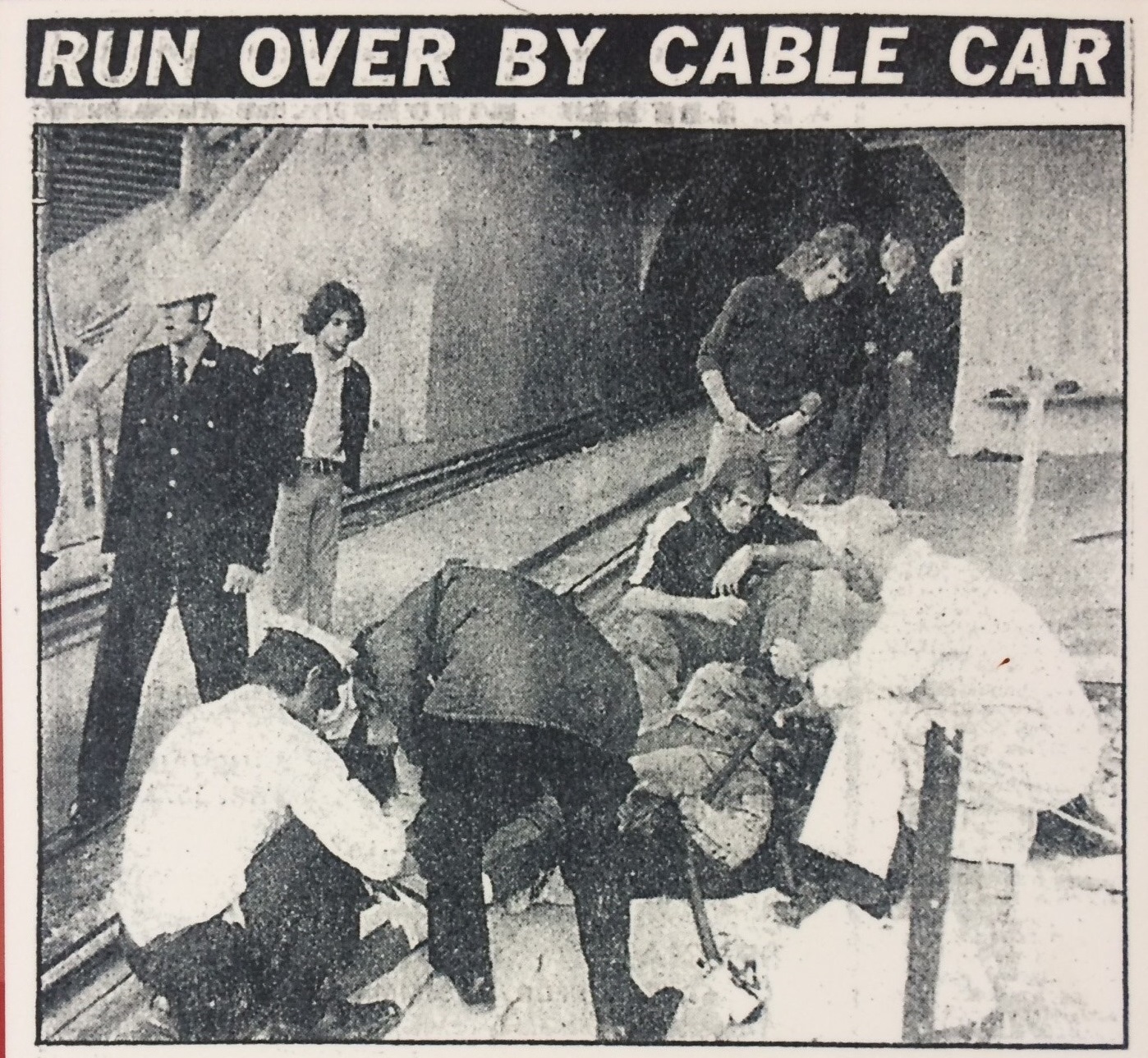

The 1973 accident was the only serious incident in the cable car’s history

FALLACY: While the best-known incident was the 1973 accident in which a construction worker was totalled after walking in front of a downward-bound cable car at Clifton Station, it was not the only significant occurrence in the line’s history. In the days of non-existent Health & Safety practices, the Cable Car was a hotbed for serious injuries and even deaths. Seriously heavy and originally incredibly cumbersome to operate, most reported incidents related to the cars’ unwieldy brakes and inability to stop promptly. This led to a record number of shattered bones, facial injuries, and compound fractures among unlucky passengers and passers-by, including the amputation of a 10-year old girl’s foot after she stepped off the carriage too early and was caught by the wheels. Several deaths also occurred on the line, the first recorded in the minutes of the company’s annual meeting in 1905 [E2] , with three further deaths in 1918, 1931 and 1932.

Despite being less grisly compared to previous incidents, the accident in 1973 tends to overshadow earlier accidents due to the significant impact it had on the Cable Car. Not only did it trigger a serious investigation and see the closure of the line in 1978, but it brought the city to rally behind the continued service the cars provided, eventually leading to the introduction of the fenced tracks and enclosed carriages we know today.

So, there you have it – the top five Cable Car urban legends laid out and laid bare. Have you got any other local myths you’re curious about? Pop into Wellington Museum or the Cable Car Museum and have a chat to the staff behind the counters – you may be surprised by what you find out!

This post is written by Jay Èvett, Visitor Services Host for Museums Wellington and Director of Te Pāhi Pōneke | Wellington Historical Theatre Co. Special thanks to Alice Moss-Baker for her tireless work helping find the truth behind these tales.

BOOK REFERENCE:

[E1] Kevin Bourke, Kelburn, King Dick and the Kelly Gang: Richard Seddon and political patronage (Wellington: Hit or Miss Publishing 2008), p.150

[E2] Perfect, Colin (Prepared for the Wellington Museums Trust). Conservation Plan and Restoration Review for Kelburn Cable Tramway Gripcar 3. 2007. ISBN 978-0-473-12203-4

Leave a comment